Recognizing Functional Neurological Disorder: A Quick Guide

This guide is based on established clinical resources, including educational materials developed by Professor Jon Stone.

FND is defined as a disorder of the voluntary motor or sensory system, which has been linked to corrupt communication between systems in the brain. The diagnosis relies on identifying positive clinical signs, confirming the disorder of brain function.

A Brief History of Terminology

Functional Neurological Disorder is an ancient illness that has suffered from centuries of misunderstanding and medical neglect. The different names used throughout history reflect the long-standing stigma:

- Hysteria (Ancient Greece): The first term, linked to the word for ‘uterus,’ originally connected the condition solely to women and reproductive organs.

- Conversion Disorder (20th Century): Suggested that repressed emotional conflict was being “converted” into physical symptoms, contributing to the misconception that FND is purely psychological.

- Functional Neurological Disorder (FND): The modern, preferred term. It removes the psychological assumption and reflects the scientific understanding that the symptoms are caused by a verifiable, involuntary problem with the functioning (or “software”) of the brain and nervous system.

This long history of stigma is why FND CONNECT emphasizes clear, accurate, and compassionate language.

How a Neurologist Diagnoses FND

Functional Neurological Disorder is a clinical diagnosis—meaning it is made based on what the neurologist observes, not just by ruling out other conditions. The diagnosis relies on finding **positive, verifiable clinical signs** during the examination.

Steps for Diagnosis:

- Detailed History and Physical Exam: The neurologist conducts an in-depth review of symptoms and performs a thorough physical and neurological examination.

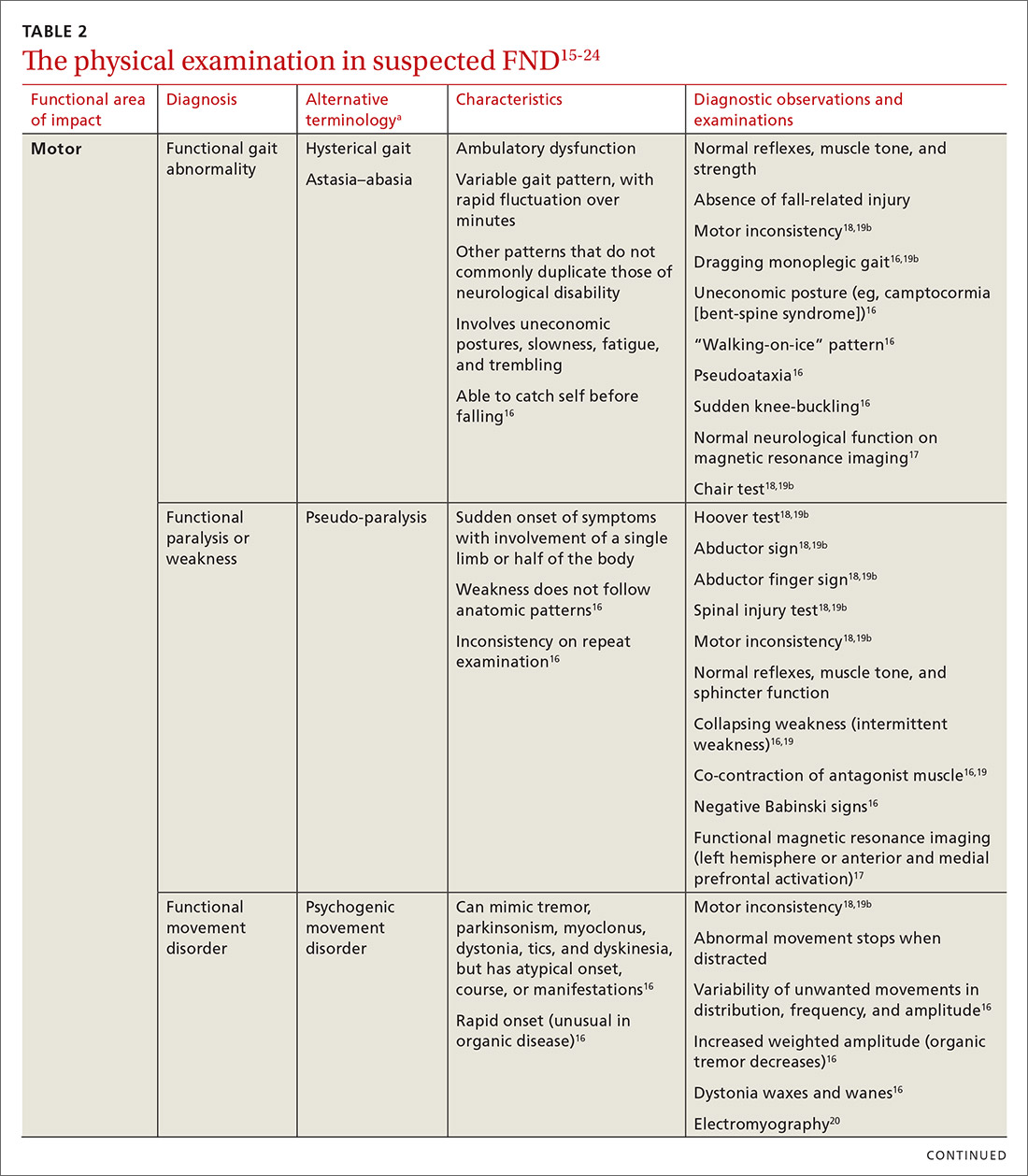

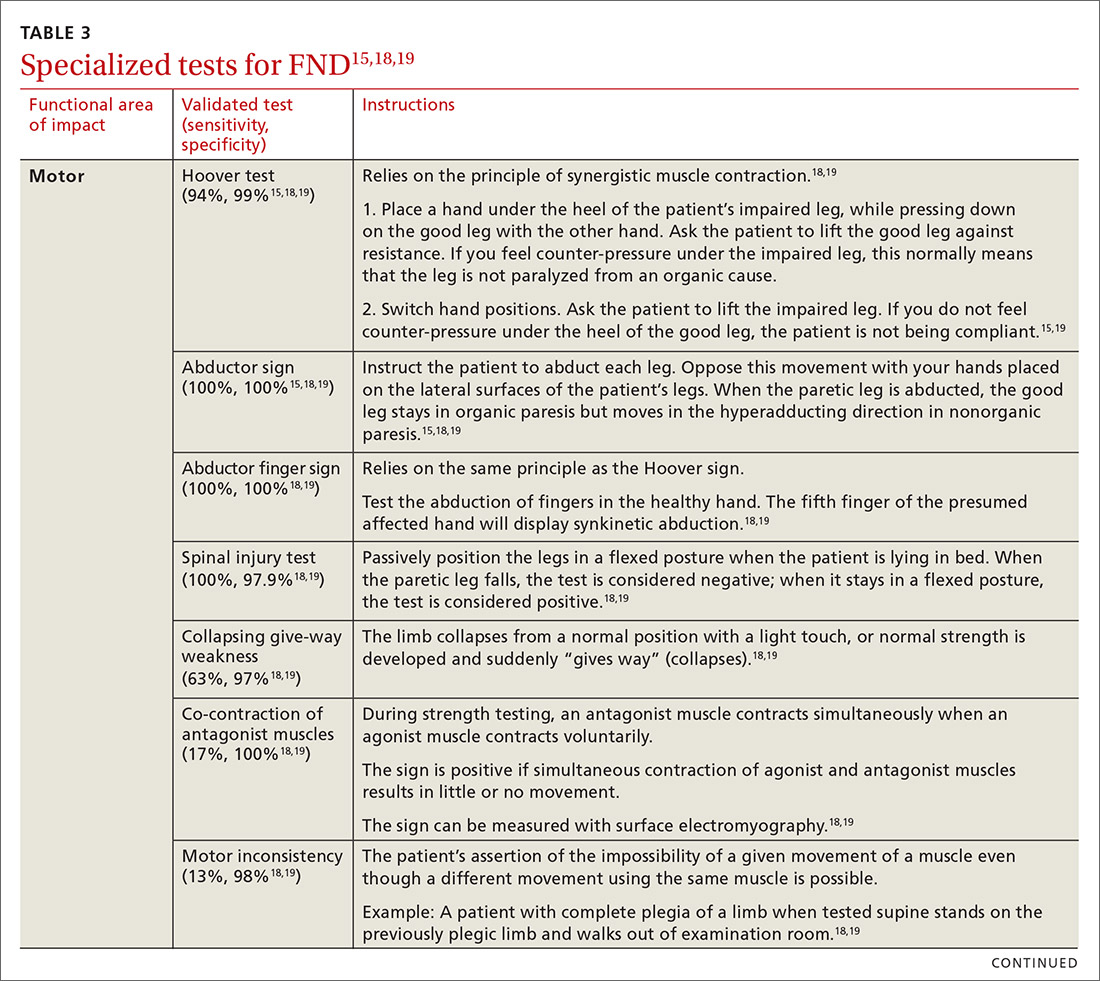

- Searching for Positive Signs: The neurologist actively looks for positive clinical signs that are characteristic of FND, such as Hoover’s sign or tremor entrainment.

- Rule-Out Testing: Tests like MRI, EEG, and blood tests are used to confidently rule out other structural, electrical, or metabolic conditions that could mimic FND.

- Confirming the Diagnosis: The diagnosis is made based on the combination of the observed positive clinical signs and the absence of findings for other neurological disorders on the medical tests.

The ultimate goal is certainty: FND is a clinical diagnosis made based on what is present, not just what is absent.

Key Areas of Assessment

Diagnosis involves assessment across four main areas:

| Area | What to Look For |

|---|---|

| Patient History | Multiple Symptoms are common, including motor/sensory symptoms, fatigue, pain, and sleep/dissociative symptoms. |

| Ability | Look for the consistency between what the patient can do automatically versus voluntarily. |

| Onset | Often follows a physical trigger (like a migraine, injury, or syncopal episode). Previous adverse experiences are a risk factor but not always present. |

| Examination | Diagnosis is based on identifying positive clinical features (signs present during the exam), not just ruling out other neurological diseases. |

2. Positive Diagnostic Signs (The Evidence)

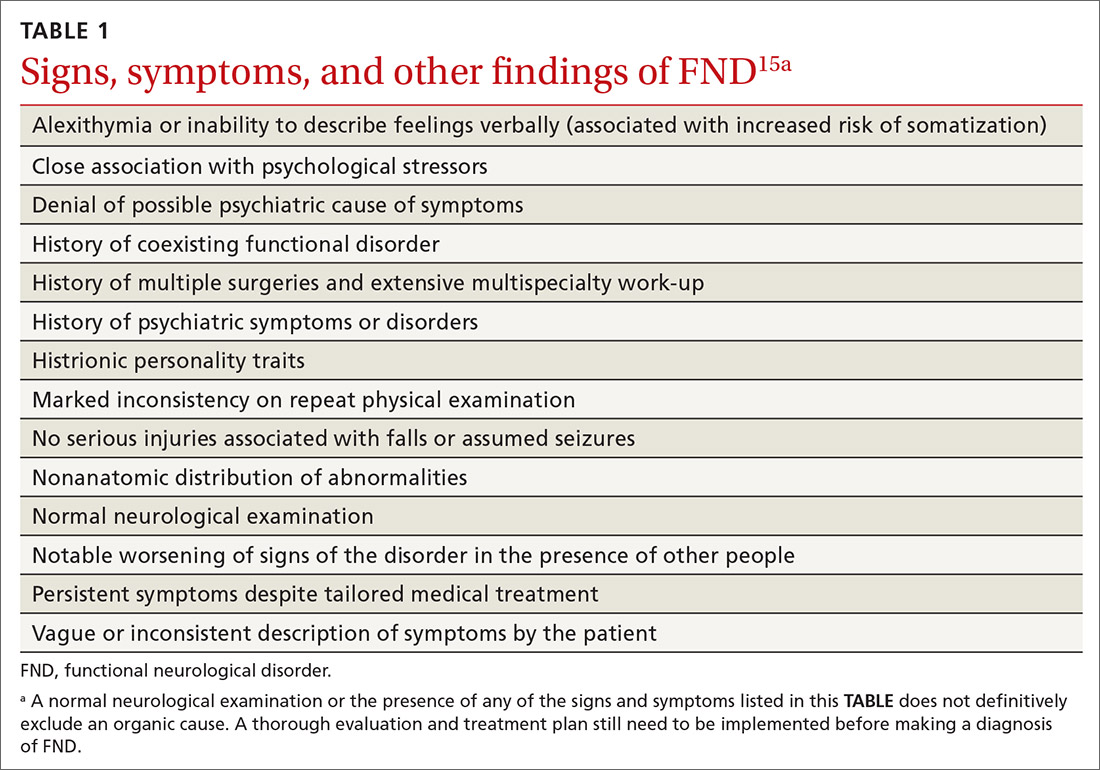

FND is characterized by identifiable clinical signs that are inconsistent with typical neurological disease.

| Symptom Category | Key Positive Clinical Sign |

|---|---|

| Functional Weakness | Hoover’s Sign: When the patient pushes down with their unaffected leg, the weakness in the affected leg momentarily improves or disappears. |

| Functional Movements | Often presents as Fixed Postures (e.g., a clenched fist or inverted ankle) or Tremor that stops or changes when the patient is distracted. |

| Functional Seizures | Features include eyes kept tightly closed, side-to-side head shaking, and often a longer duration than typical epileptic seizures. |

| Functional Vision | Tubular Visual Field: The patient reports a reduced visual field that remains the same size regardless of how far the object is held from the face. |

⚠️ Common Pitfalls (Why Misdiagnosis Happens)

It is important to avoid making a diagnosis based on these reasons:

- Assuming the symptoms are psychological simply because a mental health comorbidity exists (e.g., anxiety or depression).

- Relying purely on the absence of a known neurological disease (diagnosis must be based on the positive signs above).

- Patients who do not fit a perceived “stereotypical” profile (e.g., the patient is a working male, not a female with history of trauma).

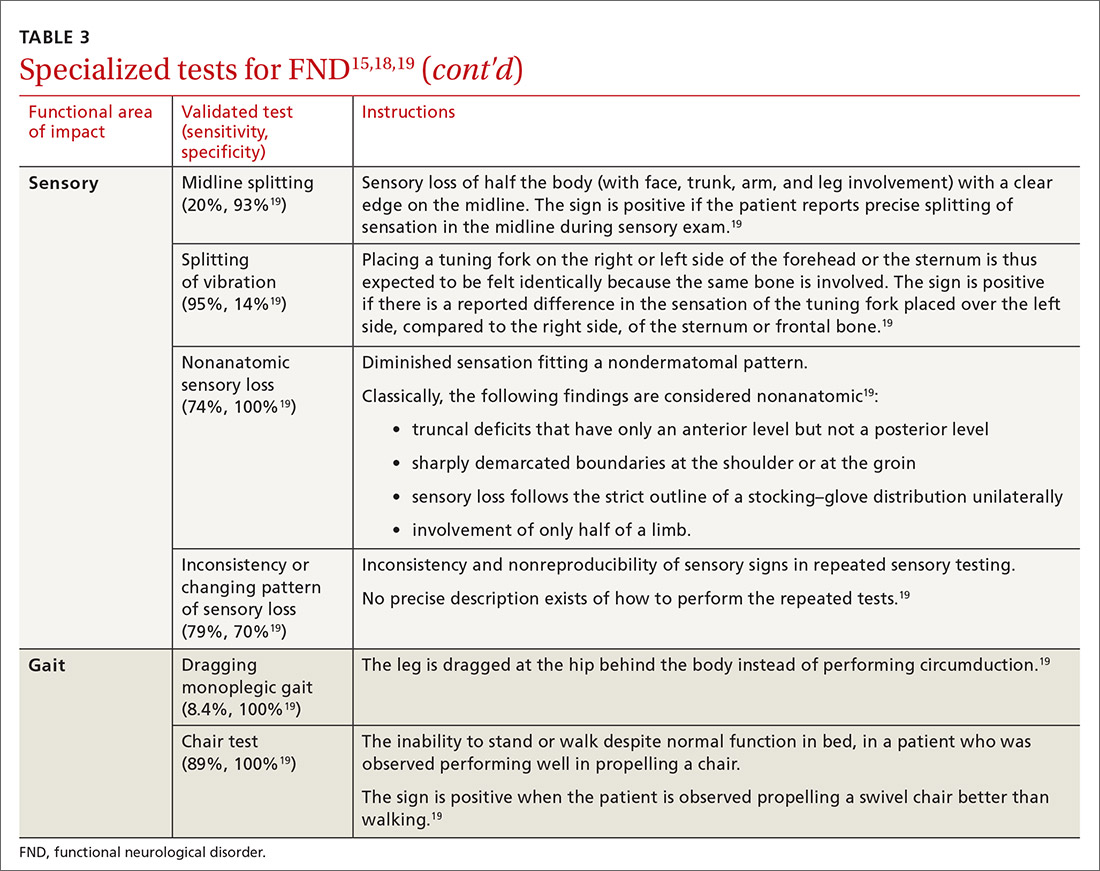

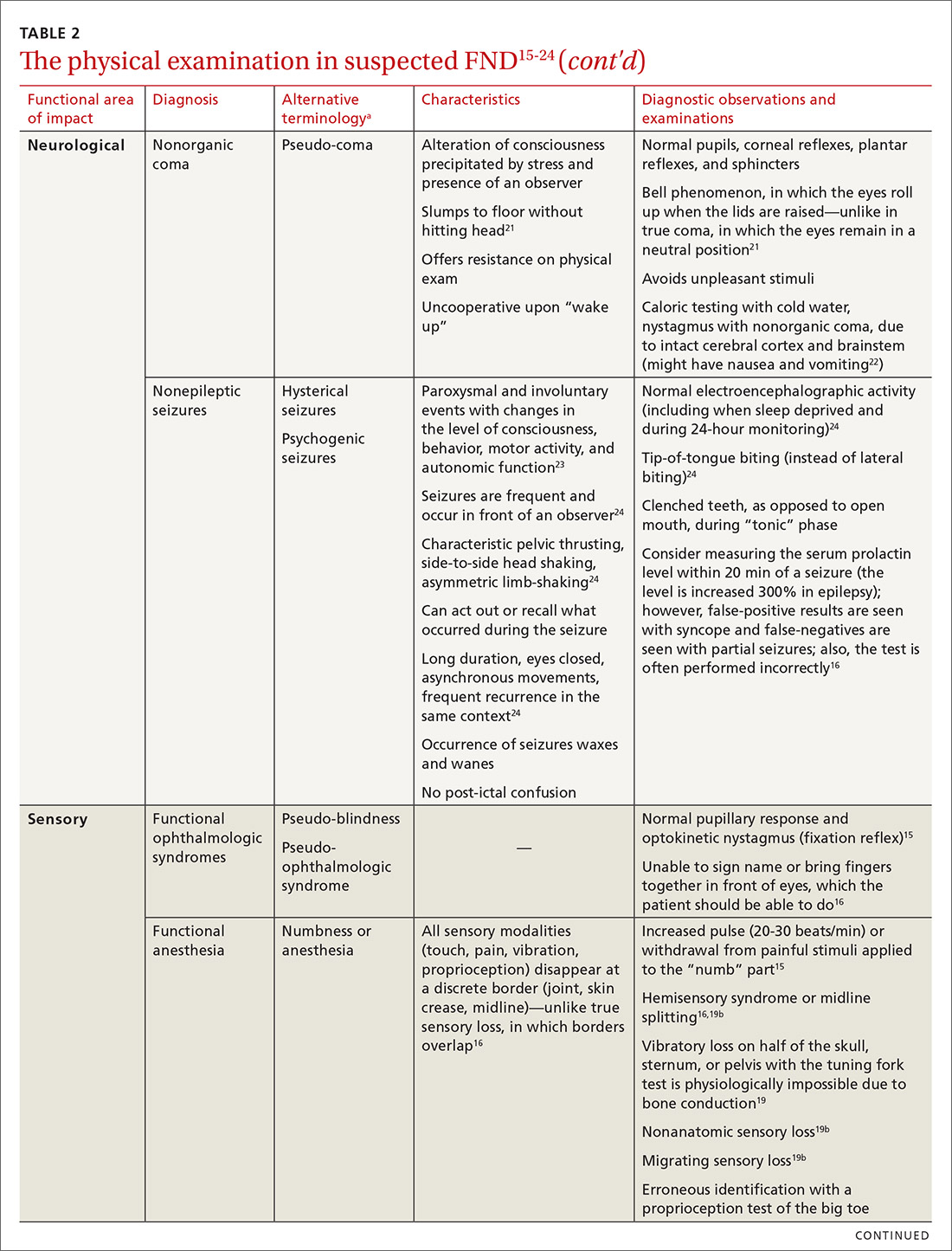

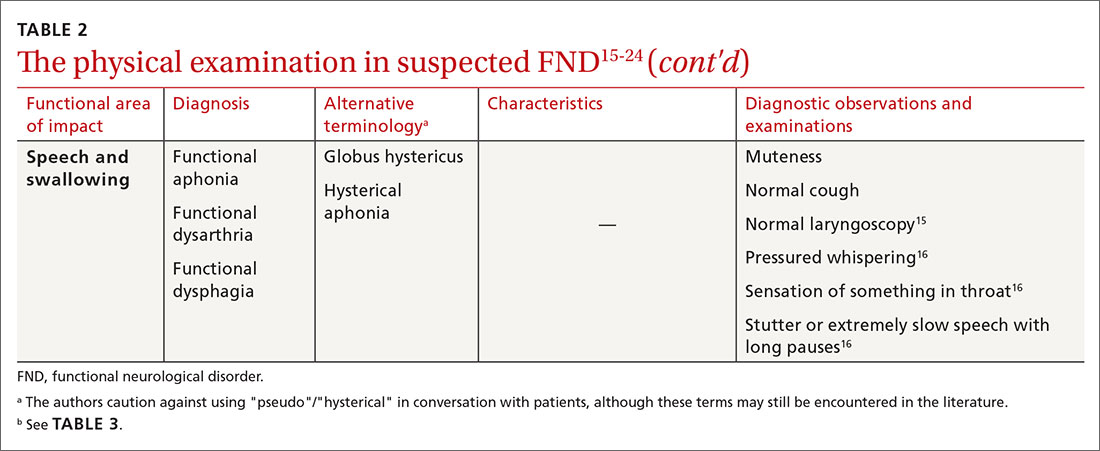

Conducting a diagnostic examination

Taking the history. Certain clues can aid in the diagnosis of FND (TABLE 1).15 For example, the patient might have been seen in multiple specialty practices for a multitude of vague symptoms indicative of potentially related conditions (eg, chronic fatigue, allergies and sensitivities, fibromyalgia, and other chronic pain). The history might include repeated surgeries to investigate those symptoms (eg, laparoscopy, or hysterectomy at an early age). Taking time and care to explore all clinical clues, patient reports, and collateral data are therefore key to making an accurate diagnosis.

A coexisting psychiatric diagnosis might be associated with distress from the presenting functional neurological symptoms—not linked to the FND diagnosis itself.

Note any discrepancies between the severity of reported symptoms and functional ability. A technique that can help elucidate a complex or ambiguous medical presentation is to ask the patient to list all their symptoms at the beginning of the interview. This has threefold benefit: You get a broad picture of the problem; the patient is unburdened of their concerns and experiences your validation; and a long list of symptoms can be an early clue to a diagnosis of FND.

Other helpful questions to determine the impact of symptoms on the patient’s well-being include inquiries about16:

- functional impairment

- onset and course of symptoms

- potential causal or correlating events

- dissociative episodes

- previous diagnoses and treatments

- the patient’s perceptions of, and emotional response to, their illness

- a history of abuse.

Some clinical signs associated with FND might be affected by other factors, including socioeconomic status, limited access to health care, low health literacy, poor communication skills, and physician bias. Keep these factors in mind during the visit, to avoid contributing further to health disparities among groups of patients affected by these problems.